Social-cognitive direction in personality research (A. Bandura, J. Rotter).

Julian Rotter is an American psychologist and author of social learning theory. His most famous work is Social Learning and Clinical Psychology (1954). Based on a number of principles of interactionism and behaviorism, D. Rotter believes that in order to predict an individual’s behavior, it is necessary to take into account 4 variables. Behavior potential – i.e. a set of human behavioral reactions in response to a situation - a stimulus (verbal, non-verbal, laughter, crying, fighting, etc.); waiting – i.e. the expectation that as a result of a given behavioral act, appropriate reinforcement will be received (based on past experience); reinforcement value – i.e. different importance of reinforcements and preference for those that seem more important to the individual (also based on past experience); psychological situation - i.e. presentation of the situation by the individual (the situation is as the person sees it and in accordance with this image of the situation the person implements his behavior). For a specific controlled situation, according to D. Rotter, the formula for predicting behavior is as follows: behavior potential = expectation + reinforcement value.

This way you can predict human behavior.

To predict behavior in everyday life, D. Rotter, based on the fact that each individual acts purposefully to satisfy his needs, put forward a more general formula of behavior:

Need potential = freedom of activity + value of need.

In other words, a person strives to achieve goals, the achievement of which will be reinforced and the expectation of reinforcement is of high value. If we know these factors, we can predict a person's behavior.

Based on this concept of personal behavior, D. Rotter identified 2 categories of people depending on the personal variable of the so-called locus of control (i.e., people’s interpretation of the determination of their behavior). Some people - externalists - believe that their behavior (successes and failures) is controlled and regulated by external factors that do not depend on them (fate, chance, luck, other influential people, etc.). Others - internals - on the contrary, are convinced that their behavior is determined by their actions, abilities, etc. Therefore, people with an internal orientation believe that they can influence reinforcements. Internality and externality as personality traits, according to D. Rotter, are continuous characteristics, i.e. All people have both orientations, but in some they are more pronounced, in others less, hence the division into internals and externals, which also differ in other parameters.

Thus, it has been established that internals are characterized by a desire to monitor their health (play sports, etc.). Externalizers are more likely to have depression, mental illness, anxiety, and fear. Internals, convinced of the possibility of building their well-being through their own efforts, are generally more adapted to complex social situations and living conditions.

In order to identify the measurement of locus of control, D. Rotter developed the “I - E Scale”.

Bandura notes that it is a common belief among psychodynamic doctrines that human behavior depends on a number of internal processes (for example, drives, drives, needs), often operating at a level below the threshold of consciousness. But the question of the conceptual and empirical basis of this point of view still remains open.

Internal determinants were often inferred from the behavior they were supposed to cause, and as a result descriptions were given in the guise of explanation. The presence of hostile impulses, for example, was inferred from an outburst of anger, which was then explained by the action of this underlying impulse. Similarly, the existence of achievement motives was inferred from achievement behavior; motives for addiction - from addictive behavior; motives of curiosity - from inquisitive behavior; motives of power - from dominant behavior and so on. There was no limit to the number of motives that could be found by inferring them from the behavior they were supposed to cause. In addition, psychodynamic theories neglected the enormous complexity and diversity of human responses. In Bandura's view, the internal reality of drives and motives simply cannot account for the apparent variation in frequency and strength of a given behavior in different situations with different people in different social roles. You can compare how a mother reacts to her child at home on different days, how she reacts to her daughter as opposed to her son in a comparable situation, and how she reacts to her child in the presence of her husband and without him. All this is a topic for thought.

Advances in learning theory have shifted the focus of causal analysis from internal forces to environmental influences (e.g., Skinner's operant conditioning). In this view, human behavior is explained by the stimuli that cause it and the reinforcing consequences that maintain it. But, according to Bandura, to explain behavior in this way is to throw out the baby with the bathwater—that is, to neglect independent cognitive processes. Radical behaviorism denied the causes of human behavior arising from internal cognitive processes. For Bandura, individuals are neither autonomous systems nor mere mechanical transmitters animating the influences of their environment - they possess superior abilities that enable them to predict the occurrence of events and create the means to exercise control over what affects their daily lives.

From Bandura's point of view, people are not controlled only by intrapsychic forces and do not only respond to external stimuli. The reasons for human functioning must be understood in terms of the continuous interaction of behavior, cognition, and environment. This approach to analyzing the causes of behavior, which Bandura designated as mutual determinism, implies that dispositional and situational factors are interdependent causes of behavior. Simply put, internal determinants of behavior, such as belief and expectation, and external determinants, such as reward and punishment, are part of a system of interacting influences that act not only on behavior, but also on various parts of the system.

Bandura's triad model of reciprocal determinism shows that while behavior is influenced by the environment, it is also partly the product of human activity, meaning people can have some influence on their own behavior. For example, a person's rude behavior at a dinner party can lead to the fact that the actions of those around him will be more likely to be a punishment than an encouragement for him. Conversely, a friendly person on the same evening may create an environment in which he receives plenty of reward and little punishment. In any case, behavior changes the environment. Bandura also argued that because of their extraordinary ability to use symbols, people can think, create, and plan, that is, they are capable of cognitive processes that constantly manifest themselves through their actions.

Sometimes the influences of the external environment are strongest, sometimes internal forces dominate, and sometimes expectations, beliefs, goals and intentions shape and guide behavior. Bandura believes that because of the dual-directional interaction between overt behavior and environmental circumstances, people are both a product and producer of their environment. Thus, social cognitive theory describes a model of reciprocal causation in which cognitive, affective, and other personality factors and environmental events operate as interdependent quantities.

Julian Rotter (p. 19161

“Trust in human relationships is a person’s generalized expectation of how much one can rely on the words, promises, spoken or written statements of another person or group of people.”

J. Rotter

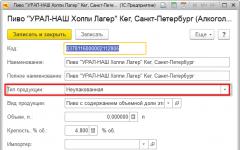

The main provisions of J. Rotter's theory of personality are presented in Fig. eleven.

Rice. P

Key Concepts

External reinforcement. Events, conditions, or actions that are valued by a person's social or cultural environment.

Internal reinforcement. The contribution of a person’s own perception to a positive or negative assessment of events.

Generalized (generalized) expectation. An expectation that extends beyond a specific situation, allowing one to use past experience to predict the possibility of future reinforcement. Generalized expectations include locus of control And interpersonal trust.

Trust in human relationships. A person's generalized expectations about the extent to which he can rely on the words, promises, or written statements of another person or group of people.

Locus of control. A term used by J. Rotter to describe a person's generalized expectations regarding the extent to which reinforcements depend on his own behavior ( internal locus of control), and in which - controlled by external forces (external locus of control).

General formula for prediction. Determining the likelihood of satisfying a specific need. The potential of a need is a function of freedom of action and the value of the need. Allows you to predict behavior in everyday life.

Expected consequence. An expectation based on previous experience that a particular behavior will lead to a specific consequence.

Expectation. A person's opinion about whether he will receive reinforcements; the likelihood, from a person's point of view, that a particular reinforcement will occur as a result of specific actions on his part in a particular situation.

The basic formula for predictions. Behavioral potential is a function of expectancy and reinforcement value. Makes it possible to predict the purposeful behavior of a person in a specific situation.

Freedom of activity. The expectation that a particular behavior will result in reinforcements associated with one of six categories of needs.

Reinforcement. Any action, condition or event that affects a person’s movement towards a goal. Vary external And internal

reinforcements Reinforcements are usually presented in the form of chains of reinforcers, which can be thought of as groups of reinforcers.

Behavior potential. The likelihood of a given behavior in a given situation due to reinforcement.

Need potential. The likelihood that a given behavior will lead to the satisfaction of a specific category of needs.

Need. In J. Rotter's theory, it is almost synonymous with goal. The author considers six categories of needs: recognition/status, dominance, independence, protection/dependence, love/affection, physical comfort. The complex of needs includes three components: the potential of the need, freedom of activity, and the value of the need.

Psychological situation. Subjective perception of environmental factors by an individual.

Freedom of activity. A variable in the general prediction formula, the average expectation regarding the achievement of positive satisfaction as a result of the implementation of actions aimed at obtaining reinforcements. Greater freedom of action reflects a person's expectation that a particular behavior will lead to success, while little freedom of activity reflects a person's expectations that a particular behavior will be unsuccessful.

The value of reinforcement. The degree to which we, given equal probability of receipt, prefer one reinforcer to another.

The value of reinforcement. A person's preference for a particular reinforcer; the extent to which a person prefers one reinforcer over another if the probability of receiving each is equal.

Need value. The degree to which a person prefers one group of reinforcers over another; the relative desirability of different reinforcers associated with different categories of needs.

- 1. Sullivan G., Rotter J., Michel W. Theory of interpersonal relations and cognitive theories of personality / G. Sullivan, J. Rottsr, W. Michel. - St. Petersburg: Prime-EUROZNAK, 2007. - 128 p.

- 2. PervinL., John O. Personality psychology: theory and research / L. Pervin, O. John; edited by V.S. Maguna. - M.: Aspect-Press, 2001.-607 p.

- 3. Frager R.. Fadiman J. Personality: theories, experiments, exercises / R. Frager, J. Fadiman. - St. Petersburg: Prime-EURO-ZNAK, 2002. - 864 p.

- 4. Kjell L., Ziegler D. Theories of personality / L. Kjell, D. Ziegler. - St. Petersburg: Peter, 2006.-607 p.

PSYCHOLOGY OF THE SUBJECT OF MANAGEMENT ACTIVITY

Subject of life and activity– a person who consciously and purposefully transforms the world around him and himself (initiator, creator, manager).

Human subjectivity– the ability of an individual to transform his own life activity into a subject of practical transformation: - the ability to manage his actions;

-really practically transform

reality;

- plan methods of action;

- implement planned programs;

- monitor progress and evaluate results

Your actions.

Formation of the subject of life and activity is the process of mastering by an individual its main structural components: meaning, goals, tasks, ways of transforming the objective world by man.

Subject of management activities shows its subjectivity in a number of dimensions (units of measurement of managerial behavior according to G. Yukl):

1) attention to discipline;

2) facilitating work;

3) problem solving;

4) goal setting;

5) role clarification;

6) emphasizing efficiency;

7) planning;

8) coordination;

9) delegation of autonomy;

10) preparation;

11) inspiration;

12) attention;

13) participation in the decision;

14) approval;

15) the possibility of varying remuneration;

16) facilitating communication;

17) representation;

18) work with information, its processing, dissemination of information;

Conflict management: transforming destructive conflicts into constructive ones.

Internality-externality (according to J. Rotter)

External or internal: where is the life control button?

USC – level of subjective control

Locus of control[from lat. locus - place, location and French. contrôle - check] - a personal characteristic that reflects the predisposition and tendency of an individual to attribute responsibility for the successes and failures of his activity either to external circumstances, conditions and forces, or to himself, his efforts, his shortcomings, to consider them as his own achievements or the results of his own miscalculations, as well as simply a lack of appropriate abilities or shortcomings.

Moreover, this individual psychological characteristic is a fairly stable, weakly changeable personal quality, despite the fact that it is finally formed in the process of socialization. In many ways, this stability of the locus of control is due to the fact that it is almost directly related to such indicators of a person’s social orientation as externality (external, or external locus of control) and internality (internal, or internal locus of control). It is generally accepted that the very concept of “locus of control” was introduced into social psychology and personality psychology by the American psychologist D. Rotter. Later, a methodological toolkit was developed that allowed the experimental psychologist, on the one hand, to determine the nature of locus control characteristic of a particular subject, and on the other, to record those patterns and dependencies that reveal the connection of this personal characteristic with others.

INTERNAL. A person with an internal locus of control. He is more self-confident, consistent, persistent in achieving his goals, prone to introspection, balanced, sociable, friendly and independent. The organizational and communication characteristics of the internal are well developed. High level of self-worth. Quite clearly, a number of experimental studies have shown that individuals who demonstrate their commitment to internal locus control, as a rule, have adequate self-esteem, they most often (if these are not purely situational circumstances) do not manifest unjustified anxiety, feelings of guilt and fear, they are inclined to fairly consistently solve assigned problems, know how to stand up for themselves, are justifiably friendly towards others, are sociable and are willing to interact on a partnership basis.

ESTERNAL. A person who is characterized by an external locus of control; they are often excessively anxious and subject to unjustified frustration, unsure both of their abilities in general and of their individual capabilities, and therefore, most often, they are not ready to solve the problems facing them in the logic of “today and here”, but rather tend to approach their solution according to "tomorrow and somewhere" scheme. They exhibit such characteristics as lack of confidence in their abilities, imbalance, the desire to postpone the implementation of their intentions indefinitely, suspicion, conflict and aggressiveness. Organizational capabilities are minimal, the ability to communicate with people is deformed. In addition, they, as a rule, are not capable of personal self-determination in a group, adequate attribution of responsibility in conditions of joint activity, and demonstrate a lack of effective group identification. It should be specially noted that the locus of control of an individual often predetermines its status in the informal power structure of the community. Thus, in groups with a high level of socio-psychological development, most often it is the internal locus of control that turns out to be one of the grounds for the individual’s psychologically favorable position, while, for example, in corporate groups, the external locus of control in combination with an official high power position, as a rule, characterizes namely the leader of the group.

Locus of control studies have been conducted mainly using the internality-externality scale developed by J. Rotter. They not only made it possible to clarify the differences between internals and externals regarding the attribution of control over one’s own life to internal or external sources, but also revealed a number of interesting patterns. Thus, B. Strickland, K. Welstone and B. Welstone found, “...that internals are more likely than externals to actively seek information about possible health problems. Internals are also more likely than externals to take precautions to maintain or improve their health, for example, by quitting smoking, starting to exercise and seeing a doctor regularly.” This means that, contrary to the image created by some writers of a convinced fatalist who is “knee-deep in the sea”, who does not part with a glass and a pipe and at the same time is distinguished by phenomenal health, in reality, the external locus of control, among other things, significantly increases the risk of serious illnesses.

Moreover, in the case of illness, the internal locus of control promotes recovery, while the external one, which in extreme cases gives rise to the so-called acquired helplessness syndrome, on the contrary, prevents it. As D. Myers notes in this regard, “in hospitals, “good patients” do not ring the bell, do not ask questions, do not control what happens. Such passivity may be good for the “efficiency” of the hospital, but bad for people. A sense of power and the ability to control one's life promotes health and survival."

The relationship between the type of locus of control and the mental health of the individual has also been recorded. In particular, "research...shows that people with an external locus of control are more likely to have mental health problems than people with an internal locus of control. For example, Fares reports that anxiety and depression are higher in externalists and lower self-esteem than in internalists." Also, internals are less likely to develop mental illness than externals. It has even been shown that the suicide rate is positively correlated (r = 0.68) with the average level of externality in the population.”

In addition, internality and externality are clearly related to the problem of conformity and nonconformism. According to L. Kjell and D. Ziegler, "...numerous studies show that externals are much more susceptible to social influence than internals. Indeed, Fares found that internals not only resist external influence, but also, when the opportunity arises, try control the behavior of others. Internals also tend to like people they can manipulate and dislike those they cannot influence. In short, internals appear to be more confident in their ability to solve problems than externals and are therefore independent. the opinions of others."

Despite the fact that from all that has been said, the conclusion suggests itself about the preference of an internal locus of control over an external one, it would be deeply erroneous to perceive externality as a terrible and irreversible “curse”, and internality, on the contrary, as a “blessing of the good fairy”.

First of all, internality and externality are not personality traits - innate and unchangeable. In his works "...Rotter clearly shows that externals and internals are not “types”, since each has characteristics not only in its category, but also, to a small extent, in the other. The construct should be considered as a continuum, having at one end expressed “externality”, and on the other - “internality”, while people’s beliefs are located at all points between them, mostly in the middle.” 312 It is this kind of “confusion” of internality and externality, characteristic of most people, that underlies the repeatedly experimentally recorded phenomenon known in social psychology as a predisposition in favor of one’s self.

The essence of this phenomenon is that people tend to see the reasons for their success in their own abilities, personal qualities, efforts, i.e. they use an internal locus of control and, conversely, attribute failures to external causes, resorting to an external locus of control. Moreover, this is observed even in cases where the social cost of an error is negligible. In one study, fourth-year psychology students were asked to complete a moderately difficult creative task on their own for a week. They were told that the assignment was optional, i.e., not required, and failure to complete it would in no way affect the student’s performance. As expected, the vast majority of students ignored the task. When answering the question about the reasons for not completing a task, less than 10% of respondents indicated internal determinants such as “reluctance,” “laziness,” and “lack of interest.” All the rest referred to external circumstances - from the banal “lack of time” to “the bad character of the head of the university library.” Those who completed the task, without exception, justified their actions with internal reasons: the desire to learn something new, the habit of completing everything, interest, etc.

Thus, most people are simultaneously characterized, to one degree or another, by both internality and externality, and the boundary between them is fluid - in some cases the internal locus of control dominates, in others the external locus of control. In addition, some modern research suggests that the predominance of internality or externality is due to social learning. Thus, in the course of studying the relationship between the locus of control and the attitude towards one’s own health, R. Lo, “...comparing externals and internals, found that the latter were more encouraged by their parents if they looked after their health - adhered to a diet, brushed their teeth well, have been seen regularly by the dentist. As a result of this early experience, internals are more aware than externals of what can cause disease and are more concerned about their health and well-being.” 313 This means there is a potential for shifting locus of control through social relearning. It is no coincidence that self-efficacy, the increase of which is the main goal of psychotherapy, from the point of view of A. Bandura, in modern social psychology is directly related to the locus of control.

For a practical social psychologist, it is extremely important to take into account the fact that such an individual psychological characteristic as locus of control in conditions of real interaction within a contact group is most often associated with the readiness and ability of specific members of society to adequately attribute responsibility for success and failure in joint activities and communication .

Who are we – hostages of life’s circumstances or masters of our destiny? Is what happens to us the result of external forces or our own activity (inactivity)? Each of us answers these questions differently. Depending on what answers we give to them, we are divided into externals and internals.

The American psychologist Julian Rotter first divided people into these two categories in the middle of the last century. He also introduced the concept of “locus of control,” which characterizes an individual’s ability to attribute his successes or failures to internal or external factors.

Julian Rotter's theory is based on the assumption that cognitive factors contribute to shaping a person's response to environmental influences. Rotter rejects the concept of classical behaviorism, according to which behavior is formed by immediate reinforcements, certainly originating from the environment, and believes that the main factor determining the nature of a person’s activity is his expectations about the future.

Rotter's main contribution to modern psychology, of course, was the formulas he developed, on the basis of which it is possible to predict human behavior. Rotter argued that the key to predicting behavior lies in our knowledge, past history, and expectations, and insisted that human behavior can best be predicted by considering the person's relationship with his or her significant environment.

D. Rotter’s theory has several important features:

Theory as a construct. Development of a system of concepts that would have predictable usefulness.

Description language. Formulating concepts that are free from uncertainty and ambiguity.

Use of operational definitions that establish the actual measurement operations for each concept.

Most human behavior is acquired or learned. This occurs in a personally meaningful environment, replete with social interactions with other people. The main feature of this theory is that it involves two types of variables: motivational (reinforcement) and cognitive (expectancy). It is also distinguished by the use of the empirical law of effect. A reinforcer is anything that causes movement toward or away from a goal. The theory places primary importance on the performance rather than the acquisition of behavior. According to T. s. n., social behavior personal. can be explored and described using the concepts of “behavioral potential”, “expectation”, “reinforcement”, “value of reinforcement”, “psychological situation”, “locus of control”.

Four concepts or variables for predicting an individual's behavior:

Behavioral potential

This variable characterizes the potential of any behavior in question to arise in a particular situation in connection with the pursuit of a particular reinforcer or set of reinforcers. In this case, behavior is defined broadly and includes motor acts, cognitive activity, verbalizations, emotional reactions, etc.

Expectancy This is an individual's assessment of the likelihood that a particular reinforcer will occur as a result of a specific behavior performed in a particular situation. Expectations are subjective and do not necessarily coincide with actuarial probability, which is calculated in an objective manner based on previous reinforcement. The individual's perceptions play a decisive role here.

Reinforcement value It is defined as the degree of preference given by an individual to each of the reinforcers, given hypothetically equal chances of their occurrence.

The psychological situation itself is an important predicting factor

To accurately predict behavior in a situation, it is necessary to understand the psychological significance of the situation in terms of its impact on both the value of reinforcers and expectations.

Components: the potential of the need, its value and freedom of action.

In combination, they form the basis of the general forecast formula:

The need potential is a function of the freedom of activity and the value of the need, which makes it possible to predict the actual behavior of a person. A person tends to strive for a goal, the achievement of which will be reinforced, and the expected reinforcements will be of high value.

The basic concept of generalized expectation in T. s. n. – internal-external “locus of control”, based on two main principles. provisions:

1. People differ in how and where they localize control over events that are significant to them. There are two polar types of such localization – external and internal.

2. Locus of control, characteristic of the definition. personal, situational and universal. The same type of control characterizes the behavior of a given person. both in the case of failures and in the case of achievements, and this applies equally to diff. areas of social life and social behavior.

To measure locus of control, Rotter's Internality-Externality Scale is used.

Locus of control involves a description of the extent to which a person's feels like an active subject of his own. activities and one’s life, and in which - a passive object of the actions of other people and circumstances...

Internals not only resist outside influence, try to control the behavior of others, are confident in their ability to solve problems, and are independent of the opinions of others. Believes that success and failure are determined by her own actions and abilities. Internals function better in solitude and in the presence of the necessary degrees of freedom. They have positive self-esteem, with greater consistency between the images of the real and ideal “I”. -Take care of your mental and physical health. health

A person with an external locus of control believes that his successes and failures are regulated externally. factors (fate, luck, lucky chance); are subject to social influence - Conformal and dependent behavior is inherent - They cannot exist without communication, they work more easily under supervision and control - They are characterized by anxiety and depression, they are more prone to frustration and stress, the development of neuroses..

Externals and internals also differ in the ways of interpreting social situations, in particular, in the methods of obtaining information and in the mechanisms of their causal explanation. Internals prefer greater awareness of the problem and situation, greater responsibility than externals; in contrast to externals, they avoid situational and emotionally charged explanations of behavior.

In general, in T. s. n. emphasizes the importance of motivational and cognitive factors to explain personal behavior. in the context of social situations, an attempt is made to explain how behavior is learned through interaction with other people and elements of the environment. Empirical conclusions and methodological. tools developed in T. s. n., is actively and fruitfully used in the experiment. personality research.

His social learning theory is an attempt to explain how behavior is learned through interaction with other people and elements of the environment.

Rotter's social learning theory focuses on predicting behavior

person in difficult situations. Rotter believes that it is necessary to carefully analyze

interaction of four variables. These variables include behavioral potential, expectancy, reinforcement value, and psychological situation.

Behavior potential.

This term refers to the likelihood of a given behavior “occurring in a given situation or situations in relation to a single reinforcer or reinforcers.” Let's imagine, for example, that someone insults you at a party. How will you react? From Rotter's point of view, there are several responses. You can say that this is crossing all boundaries and demand an apology. You can ignore the insult and move the conversation to another topic. You can punch the offender in the face or simply walk away. Each of these reactions has its own behavioral potential. If you decide to ignore the offender, it means that the potential for that reaction is greater than any other possible reaction. Obviously, the potential for each response can be strong in one situation and weak in another. High-pitched screams and screams may have high potential in a boxing match, but very little potential at a funeral (at least in American culture).

Expectation.

According to Rotter, expectation refers to the subjective probability that a certain

reinforcement will occur as a result of specific behavior. For example, before you decide whether to go to a party or not, you are likely to try to calculate the likelihood that you will have a good time. From Rotter's point of view, the value of expectancy strength can vary from 0 to 100 (0% to 100%) and is generally based on previous experience of the same or similar situation. Rotter's expectancy concept clearly states that if people have been reinforced in the past for behavior in a given situation, they are more likely to repeat that behavior. in a situation we are faced with for the first time, the expectation is based on our experience in a similar situation. A recent college graduate who received praise for working on a semester test over the weekend probably expects to be rewarded for finishing a report for his boss over the weekend. This example shows how waiting can lead to consistent patterns of behavior, regardless of time or situation. In fact, Rotter says that a stable expectation, generalized on the basis of past experience, does explain the stability and unity of personality. However, it should be noted that expectations do not always correspond to reality.

Rotter makes a distinction between those expectations that are specific to one situation and those that are most general or applicable to a range of situations. The first, called specific expectations, reflect the experience of one specific situation and are not applicable to the prediction of behavior. The latter, called generalized expectations, reflect experience in various situations and are very suitable for studying personality in Rotter's sense. Later in this section we will look at a generalized expectancy called internal-external locus of control.

The value of reinforcement.

Rotter defines reinforcement value as the degree to which we, given equal

probability of obtaining, we prefer one reinforcement to another. Using this concept, he argues that people differ in their assessment of the importance of an activity and its results. Given the choice, for some, watching basketball on television is more important than playing bridge with friends.

Like expectations, the value of different reinforcers is based on our previous

experience. Moreover, the reinforcement value of a particular activity may vary from

situation to situation and over time. For example, social contact is likely to be more valuable if we are lonely and less valuable if we are not lonely. However, Rotter argues that there are relatively stable individual differences in our preference for one reinforcer over another. Some people always take free tickets to a movie rather than to an opera. Accordingly, forms of behavior can also be traced in relatively stable emotional and cognitive reactions to what constitutes the main rewarded activities in life.

It should be emphasized that in Rotter's theory the value of reinforcement does not depend on

expectations. In other words: what a person knows about the value of a particular reinforcer in no way indicates the degree of expectation of this reinforcement. A student, for example, knows that good academic performance is of high value, and yet the expectation of getting high grades may be low due to his lack of initiative or ability. According to Rotter, the value of reinforcement is related to motivation, and expectancy is related to cognitive processes.

Psychological situation.

Rotter argues that social situations are as the observer perceives them to be. Rotter emphasizes the important role of situational context and its influence on human behavior. He builds a theory that a set of key stimuli in a given social situation causes a person to expect the results of behavior - reinforcement. Thus, a student might expect to perform poorly in a social psychology seminar, resulting in her professor giving her a low grade and being ridiculed by her peers. Therefore, we can predict that she will drop out of school or take some other action aimed at preventing the expected unpleasant outcome.

The theme of human interaction with the environment that is significant to him is deeply embedded in

Rotter's vision of personality. As an interactionist, he argues that the psychological situation must be considered along with expectations and the value of reinforcement, predicting the possibility of any alternative behavior. He subscribes to Bandura's view that personal factors and environmental events interact best to predict human behavior.

Basic formula for predicting behavior.

In order to predict the potential of a given behavior in a specific situation, Rotter proposes the following formula:

Behavior potential = expectancy + reinforcement value.

It should be noted that Rotter's basic formula is a hypothetical rather than a pragmatic means of predicting behavior. In effect, it suggests that the four variables we just looked at (behavioral potential, expectancy, reinforcement, psychological situation) are only useful for predicting behavior under carefully controlled conditions, such as in a psychological experiment.

General forecast formula

Rotter believes that his basic formula is limited to the prediction of a specific

behavior in controlled situations where reinforcements and expectations are relatively simple. Forecasting behavior in everyday situations, from his point of view, requires a more generalized formula. Therefore, Rotter proposes the following forecast model.

Need potential = freedom of activity + value of need.

This equation shows that two separate factors determine the potential

building behavior aimed at satisfying certain needs. The first factor is a person’s freedom of activity or the general expectation that a given behavior will lead to the satisfaction of a need. The second factor is the value that a person attaches to the need associated with the expectation or achievement of certain goals. Simply put, Rotter's general prediction formula means that a person tends to pursue goals that will be reinforced, and the expected reinforcers will be of high value. According to Rotter, provided we know these facts, an accurate prediction about how a person will behave is possible.

The general prediction formula also highlights the influence of the generalized expectation that reinforcement will occur as a result of a particular behavior in different situations. Rotter identified two such generalized expectations: locus of control and interpersonal trust. Locus of control, discussed next, is the basis of the Rotter Internal-External Scale, one of the most widely used self-report measures in personality research.

Locus of control is a personality variable. A central construct of social learning theory, locus of control is a generalized expectation of the extent to which people control reinforcements in their lives. People with an external locus of control believe that their successes and failures are regulated by external factors such as fate, luck, luck, influential people, etc. “Externalists” believe that they are hostages of fate. In contrast, people with an internal locus of control believe that success and failure are determined by their own actions and abilities (internal, or personality factors).

Rotter clearly shows that externalities and internals are not “types”, the Construct should be viewed as a continuum with a pronounced “externality” at one end and an “internality” at the other, with people’s beliefs located at all points in between, for the most part in the middle. In other words, some people are very external, some are very internal, and the majority are between the two extremes.

Measuring locus of control. Although there are several ways to measure control orientation, the most commonly used is the I-E Scale created by Rotter. Researchers using the I-E scale typically identified subjects whose scores were at the extreme ends of the distribution (eg, above the 75th percentile or below the 25th percentile). These subjects were classified as either externalizers or internalizers, and those whose results fell in between were excluded from further study. The researchers then continued to look for differences between the two extreme groups by measuring other self-report measures and/or behavioral responses.

SOCIAL LEARNING THEORY (J. Rotter)

T.s. n. - cognitive theory of personality. second half of the 20th century, developed by Amer. personologist Rotter. According to T. s. n., social behavior personal. can be explored and described using the concepts of “behavioral potential”, “expectancy”, “reinforcement”, “value of reinforcement”, “psychological situation”, “locus of control”. “Behavioral potential” refers to the likelihood of behavior occurring in reinforcement situations; it is implied that every person has a certain. potential and a set of actions and behaviors. reactions formed during life. “Waiting” in T. s. n. refers to the subject, the probability that the determined. reinforcement will be observed in behavior in similar situations. A stable expectation, generalized on the basis of past experience, explains the stability and integrity of the individual. In T. s. n. There are differences between expectations that are specific to one situation (specific expectations), and expectations that are more general or applicable to a number of situations (generalized expectations), reflecting the experience of various people. situations. The “psychological situation” is as it is perceived by the individual. A particularly important phenomenon. the role of situational context and its influence on human behavior. and for psychology. situation.

Rotter defines “reinforcement value” as the degree to which personal with an equal probability of receiving reinforcement, prefers one reinforcement to another. On people's behavior. influences the value of the expected reinforcement. Different people value and prefer different reinforcements: some value praise, respect from others more, others value material values or are more sensitive to punishment, etc. There are relatively stable individuals, differences in personality. preference for one reinforcer over another. Like expectations, the value of reinforcement is based on personal experience. and can change over time and from situation to situation. Moreover, the value of reinforcement does not depend on expectation. It is associated with motivation, and expectation is associated with cognitive processes. Predicting the likelihood of personal behavior. in a certain situation is based on two fundamentals. variables - expectation and value of reinforcement. In T. s. n. a formula is proposed for predicting personal behavior, based on the basic. concepts of theory:

behavioral potential = expectancy + reinforcement value.

Behavioral potential includes five potential “techniques of existence”: 1) behavioral. reactions aimed at achieving success and serving as the basis for social recognition; 2) behavioral reactions of adaptation, adaptation, which are used as techniques for coordinating with the requirements of other people, societies, norms, etc.; 3) protective behavior. reactions used in situations where the requirements exceed the capabilities of people. at the moment (for example, reactions such as denial, suppression of desires, devaluation, shading, etc.); 4) avoidance techniques - behavioral. reactions aimed at “exiting the field of tension”, leaving, escape, rest, etc.; 5) aggressive behavior. reactions - it can be physical. aggression, and symbolic. forms of aggression such as irony, ridicule, intrigue, etc.

Rotter believed that people always strive to maximize rewards and minimize or avoid punishment. The goal determines the direction of a person’s behavior. in search of satisfaction needs, which determine a set of different types of behavior, including, in turn, various. sets of reinforcements.

In T. s. n. six types of needs are identified that apply to the prediction of behavior: 1) “recognition status,” meaning the need to feel competent and recognized as an authority in a wide range of activities; 2) “protection-dependence”, which determines the need for personal in protecting yourself from troubles and expecting help from others in achieving significant goals; 3) “dominance,” which includes the need to influence the lives of other people, control them and dominate them; 4) “independence”, which defines the need to make independent decisions and achieve goals without the help of others; 5) “love and affection,” including the need for acceptance and love from others; 6) “physical comfort”, including the need for physical activity. safety, health and freedom from pain and suffering. All other needs are acquired in connection with those mentioned and in accordance with the satisfaction of the basic ones. personal needs in physics health, safety and pleasure.

potential of the need = freedom of activity + value of the need.

The need potential is a function of the freedom of activity and the value of the need, which makes it possible to predict the actual behavior of a person. A person is inclined to strive for a goal, the achievement of which will be reinforced, and the expected reinforcements will be of high value.

The basic concept of generalized expectation in T. s. n. - internal-external “locus of control”, based on two main principles. provisions: 1. People differ in how and where they localize control over events that are significant to them. There are two polar types of such localization - external and internal. 2. Locus of control, characteristic of the definition. personal, supra-situational and universal. The same type of control characterizes the behavior of a given person. both in the case of failures and in the case of achievements, and this applies equally to diff. areas of social life and social behavior.

To measure locus of control, or, as it is sometimes called, the level of subjective control, Rotter's Internality-Externality Scale is used. Locus of control involves a description of the extent to which a person's feels like an active subject of his own. activities and one’s life, and in which - a passive object of the actions of other people and circumstances. Externality - internality of phenomena. a construct, which should be considered as a continuum, having at one end a pronounced “externality”, and at the other - “internality”; People's beliefs are located at all points between them, for the most part in the middle.

Personal is able to achieve more in life if she believes that her destiny is in her own. hands. Externals are much more susceptible to social influence than internals. Internals not only resist outside influence, but also, when the opportunity arises, try to control the behavior of others. Internals are more confident in their ability to solve problems than externals and are therefore independent of the opinions of others.

Personal with an external locus of control believes that her successes and failures are regulated externally. factors such as fate, luck, chance, influential people and unpredictable environmental forces. Personal with an internal locus of control believes that success and failure are determined by her own actions and abilities.

Externals are characterized by conformal and dependent behavior. Internals, unlike externals, are not inclined to subordinate and suppress others, and resist when they are manipulated and tried to deprive them of degrees of freedom. Externals cannot exist without communication; they work more easily under supervision and control. Internals function better in solitude and in the presence of the necessary degrees of freedom.

Externals are more likely to experience psychol. and psychosomatic problems than internals. They are characterized by anxiety and depression, they are more prone to frustration and stress, and the development of neuroses. A connection has been established between high internality and positive self-esteem, with greater consistency between the images of the real and ideal “I”. Internals exhibit a more active position in relation to their mental health than that of externals. and physical health.

Externals and internals also differ in the ways of interpreting social situations, in particular, in the methods of obtaining information and in the mechanisms of their causal explanation. Internals prefer greater awareness of the problem and situation, greater responsibility than externals; in contrast to externals, they avoid situational and emotionally charged explanations of behavior.

In general, in T. s. n. emphasizes the importance of motivational and cognitive factors to explain personal behavior. in the context of social situations, an attempt is made to explain how behavior is learned through interaction with other people and elements of the environment. Empirical conclusions and methodological. tools developed in T. s. n., is actively and fruitfully used in experiments and personality studies.

History of Modern Psychology Schultz Duan

Julian Rotter (1916-)

Julian Rotter (1916-)

Julian Rotter was born in Brooklyn, New York, and while still in school began reading books on psychoanalysis by Sigmund Freud and Alfred Adler. Then he told himself that he wanted to become a psychologist. But in those days, during the Great Depression, there was no work for a psychologist, and so he decided to study chemistry at Brooklyn College instead of psychology. It was during this time that he met Adler (see Chapter 14) and eventually switched to psychology - even though he was clearly aware of the impracticality of this choice. He aspired to an academic career, but widespread anti-Semitic prejudice prevented him from achieving this goal. “Both at Brooklyn College and later in graduate school, I was openly warned that it was very difficult for Jews to get jobs in science, despite all their degrees. And this warning was completely justified” (Rotter. 1982. P. 346).

After Rotter received his PhD from Indiana University in 1941, he found work only at a state mental hospital in Connecticut. During World War II, he worked as a psychologist in the US Army, taught at Ohio State University until 1963, and then moved to the University of Connecticut. In 1988, Rotter received the Distinguished Scientific Achievement Award from the American Psychological Association.

Cognitive processes

Rotter was the first to use the term “social learning theory” (Rotter. 1947). He developed a cognitive approach to behaviorism, which, like Bandura's approach, assumed the existence of internal subjective experiences. Thus, his behaviorism (like Bandura's behaviorism) is less radical than Skinner's behaviorism. Rotter criticized Skinner for studying individuals in isolation and insisted that people initially learn behaviors from social experience. Rotter's approach is based on the rigorous, strictly controlled laboratory research that is so characteristic of the entire behaviorist movement - and only “experimental” people are subjected to research in conditions of social interaction.

Rotter's system considers cognitive processes more broadly than Bandura's system. Rotter believes that we all perceive ourselves as conscious beings, capable of influencing the experiences that affect our lives. Both external stimuli and the reinforcement they provide can influence human behavior, but the nature and extent of this influence is determined by cognitive factors (Rotter. 1982).

When analyzing human behavior, Rotter notes the following points:

1. We have subjective assumptions about the outcome of our behavior in terms of the quantity and quality of reinforcement that may follow that behavior.

2. We roughly estimate the likelihood that behavior of a certain kind will lead to receiving a certain reinforcement, and based on these estimates we adjust our behavior.

3. We assign different degrees of importance to different reinforcers and evaluate their relative<стоимость>in various situations.

4. Because we function in different psychological environments that are unique to us as individuals, it is obvious that the same reinforcers can have different effects on different people.

Thus, according to Rotter, our subjective experiences and expectations, which are internal cognitive states, determine how external factors will influence us.

Locus of control

Rotter's social learning theory also deals with our ideas about sources of reinforcement. Rotter's research has shown that some people believe that reinforcement depends on their behavior; about such people they say that they have internal locus of control. Others believe that reinforcement is determined only by external factors; these people have external locus of control(Rotter. 1966). behavior.

These two sources of control lead to different effects on behavior. For people with an external locus of control, their own abilities or actions do not matter much in terms of obtaining reinforcement, and therefore they make minimal or no effort to change the situation. People with an internal locus of control take responsibility for their lives and act accordingly.

Rotter's research has shown that people with an internal locus of control are healthier physically and mentally than people with an external one. People with an internal locus of control generally have lower blood pressure, are less likely to have cardiovascular disease, and have lower levels of anxiety and depression. They get better grades in school and feel they have more options in life. They have good social skills, are popular, and have higher levels of self-esteem than people with an external locus of control. University students, for example, tend to be more internally oriented than externally oriented.

Additionally, Rotter's work suggests that personality's locus of control is established in childhood based on how parents or caregivers treat the child. It turns out that parents of people with an internal locus of control are more likely to be described as helpful to their children, generous with praise for achievements (which provides positive reinforcement), consistent in their demands for discipline, and non-authoritarian in relationships.

Comments

Rotter's social learning theory has attracted many loyal followers, initially oriented toward experimental research and sharing Rotter's views on the importance of cognitive variables in influencing behavior. Rotter's research is considered so rigorous and well-controlled that it is suitable for experimental confirmation. Many scientific studies - including those related to internal or external locus of control - provide support for his cognitive approach to behaviorism. Rotter claims that his concept of locus of control has become “one of the most widely studied concepts in psychology and other social sciences” (Rotter 1990, p. 489).

From the book Consciousness and the Voice of Reason by Janes JulianJulian Jaynes CONSCIOUSNESS AND THE VOICES OF MIND Few questions have made such an interesting intellectual journey in history as that of the mind and its place in nature. Until 1859, when Darwin and Wallace independently proposed as a basis for evolution

From the book Essential Transformation. Finding an inexhaustible source author Andreas ConniraResult chain Julian Part to work with: Irritation. Intended Outcome 1: Express yourself fully. Intended Outcome 2: Perfect health and vitality. Intended Result 3: Golden blush. Core State:

From the book Introduction to Psychoanalysis by Freud SigmundPART ONE WRONG ACTIONS (1916-) PREFACE The “Introduction to Psychoanalysis” offered to the reader’s attention in no way pretends to compete with existing works in this field of science (Hitschmann. Freuds Neurosenlehre. 2 Aufl., 1913; Pfister. Die psychoanalytische Methode , 1913; Leo Kaplan.

From the book Personality Theories by Kjell LarryPART TWO DREAMING (1916)

From the book History of Modern Psychology by Schultz DuanPART THREE GENERAL THEORY OF NEUROSES (1917)

From the book Psychology in Persons author Stepanov Sergey SergeevichChapter 8. Social - cognitive direction in personality theory: Albert Bandura and Julian Rotter It is difficult to exaggerate the influence that the basic principles of learning theory have had on psychology and personality theory. Concepts of classical and operant conditioning,

From the book Personality Theories and Personal Growth author Frager RobertJulian Rotter: Social Learning Theory At the time, the late 1940s and early 1950s, when Julian Rotter began to create his theory, the most significant directions were psychoanalytic and phenomenological theories of personality. According to Rotter, both of these approaches

From the book Century of Psychology: Names and Destinies author Stepanov Sergey Sergeevich From the book The Big Book of Psychoanalysis. Introduction to psychoanalysis. Lectures. Three essays on the theory of sexuality. Me and It (collection) by Freud SigmundG. Yu. Eysenck (1916–1997) Hans Jurgen Eysenck is one of the greatest psychologists of the 20th century. He was born in Berlin, into a family whose interests were as far removed from science as possible: his mother was a film actress, a silent film star who starred in 40 films, his father was a popular entertainer.

From the author's bookChapter 24. Julian Rotter and the theory of social cognitive learning D. Chernyshev Julian Rotter’s theory is based on the assumption that cognitive factors contribute to the formation of a person’s response to environmental influences. Rotter rejects the concept

From the author's bookPart Two Dreams (1916)

From the author's bookPart Three General Theory (1917)